Image

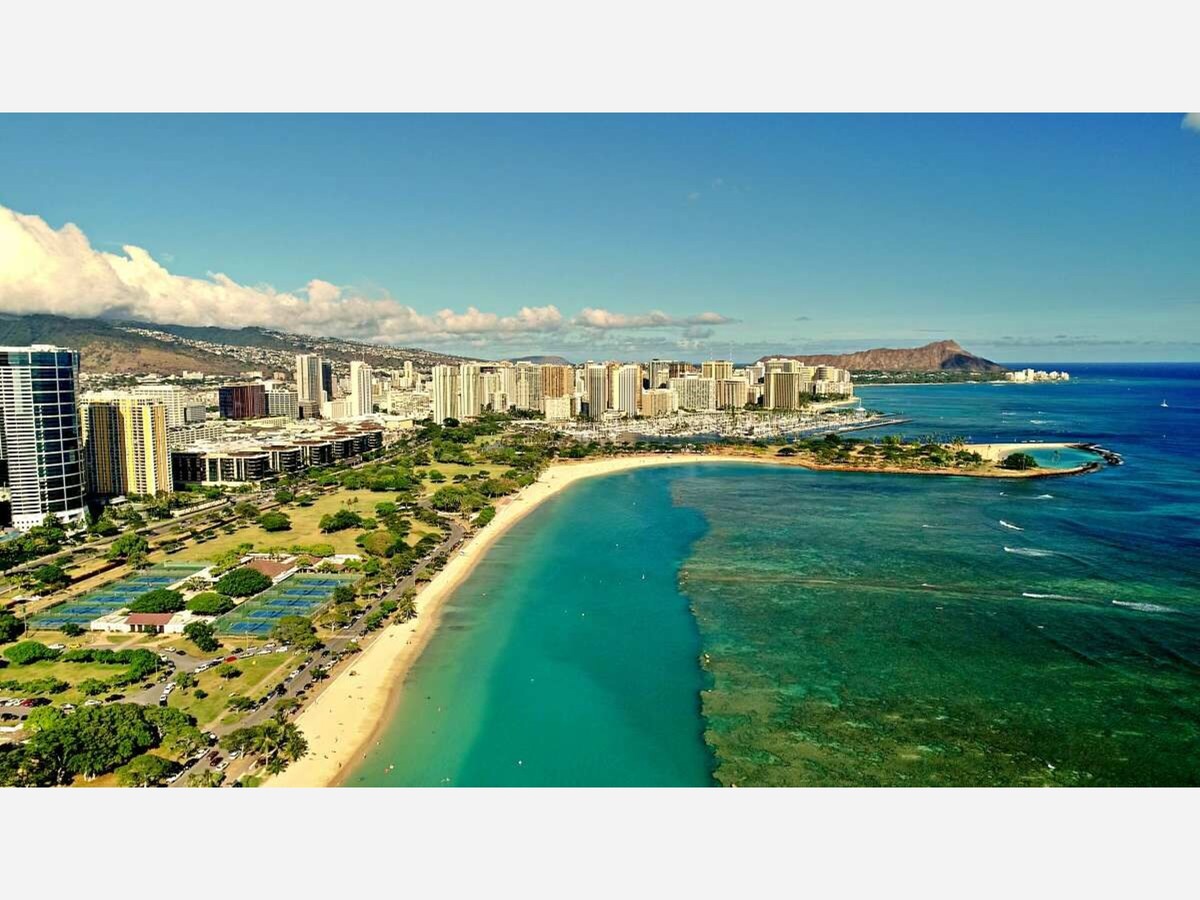

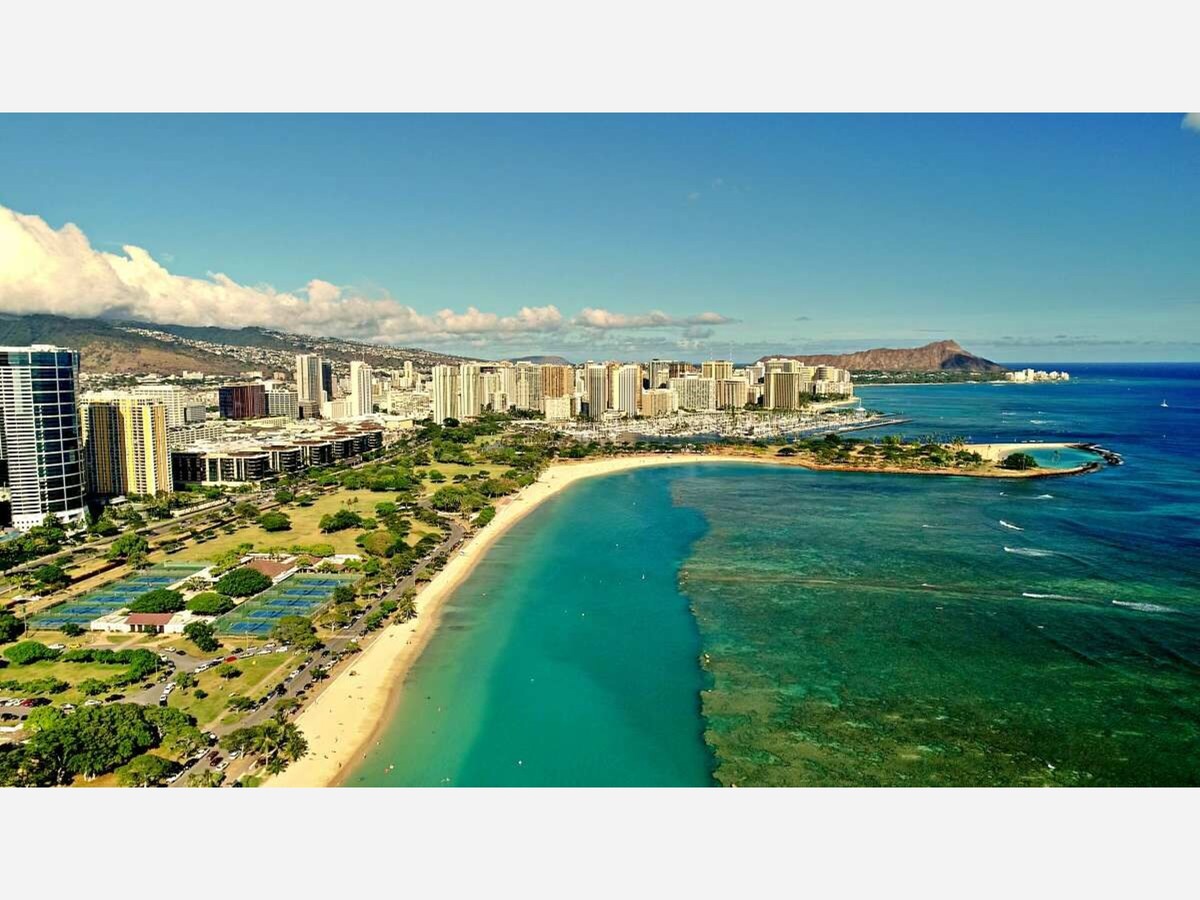

Honolulu’s coastline looks ancient, even inevitable. Palm trees line a broad sandy beach, joggers circle a calm lagoon, and families gather where the city meets the sea. To many residents and visitors alike, Ala Moana Beach Park feels as if it has always existed. Nearby, Magic Island (ʻĀina Moana) looks permanent and settled, as though it were a natural feature of the shoreline.

None of this is true.

Ala Moana Beach Park did not exist a century ago. Magic Island is not an island at all, but a man-made peninsula, physically connected to shore from the moment it was created. Both are modern constructions, built in stages from reef, rubble, and fill, shaped by war, engineering ambition, and postwar civic choices.

What makes their story remarkable is not that they were built—but that land created for military use and private development ultimately became public space, open to everyone.

Before the 20th century, the area south of today’s Ala Moana Boulevard was not a recreational shoreline. It was a broad reef flat, exposed at low tide, with coral heads, tide pools, and shallow water extending far offshore. Inland from the reef lay wetlands and low-lying coastal plain—muddy, mosquito-prone, and widely viewed as undesirable land.

There was no continuous sandy beach. There was no park. The name Ala Moana, meaning “path by the sea,” referred to a coastal route skirting this marginal landscape, not to a beachfront destination.

As Honolulu expanded in the early 1900s, these wetlands became a problem to be solved. Drainage and landfill projects began, driven by public health concerns and urban growth. Filling low-lying coastal land was seen as progress, not environmental destruction.

By the 1930s, parts of the Ala Moana area had already been reshaped, but the shoreline itself remained largely reef flat and shallow water. The idea of a major public beach had not yet fully emerged.

That changed abruptly with World War II.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Hawaiʻi came under martial law. Large portions of Oʻahu’s coastline were taken over by the U.S. military, including the Ala Moana area.

During the war:

The newly filled coastal land was used for training, drills, and staging

Civilian access was restricted or prohibited

The shoreline functioned as controlled military space, not public land

Although Ala Moana Beach Park did not yet exist, the land-in-progress was effectively off-limits. Like many coastal areas during the war, it became part of Hawaiʻi’s defensive landscape.

When the war ended, the military withdrew. Honolulu was left with newly created coastal land extending seaward over former reef flat. At that moment, the city faced a crucial choice.

This land could have become:

Industrial shoreline

Expanded port facilities

Private waterfront development

Instead, city leaders made a decision that would shape Honolulu for generations: the area would become a public park.

This was not inevitable. Across the world, reclaimed coastal land almost always became revenue-generating property. Ala Moana would become something rarer—free shoreline access in the heart of a growing city.

The creation of Ala Moana Beach Park in the mid-1950s was a two-step engineering process.

Engineers first stabilized and extended the shoreline by placing coral rubble and fill on the reef flat. This created solid ground capable of supporting trees, lawns, roads, and parking areas.

On top of this engineered base, sand was imported to form a swimmable beach. One major source was Keawaʻula Beach, commonly known as Yokohama Beach, located at the far western end of Oʻahu near Kaʻena Point. At the time, sand mining was considered acceptable and routine.

By 1955, Honolulu had gained a vast, free, urban beach park—something few American cities possessed.

Hawaiʻi became a state in 1959. Almost immediately, jet travel transformed tourism. Waikīkī filled with hotels, and planners looked westward for the next phase of development.

Just offshore from Ala Moana Beach lay more shallow reef flat. With modern engineering, it seemed entirely reasonable to create new land.

In 1962, construction began on what became known as Magic Island.

Despite the name, it was never an island. It was designed and built as a peninsula, physically connected to Ala Moana Beach Park by a narrow land bridge. There was never a channel separating it from shore.

The peninsula was formed by:

Placing massive quantities of locally dredged coral and rock

Filling the reef flat to create new land above sea level

This is an important correction to a common myth: Magic Island was not built from imported beach sand. Its mass is dredged coral fill. Sand was added later only for lagoons and small beach areas.

Magic Island was conceived not as a park, but as a future resort platform. Early plans envisioned hotels, marinas, and commercial development—a westward extension of Waikīkī.

The resort plans never materialized. Costs rose, public resistance to shoreline privatization increased, and Honolulu began to recognize the value of open space.

Rather than proceed with private development, the City made a second pivotal decision: Magic Island would be absorbed into Ala Moana Regional Park.

Land created for profit became public land instead.

The nickname “Magic Island” reflected public amazement that land had appeared where water once existed. The official Hawaiian name, ʻĀina Moana, means “land from the sea”—a literal description of its origin.

While the name is modern, it resonates with traditional Hawaiian concepts in which land and ocean are part of a continuous system. Historically, Hawaiians shaped coastlines through fishpond walls and shoreline stonework, though on a far smaller scale.

By the 1970s, Ala Moana Beach experienced erosion. To replenish it, the City turned to Mokuleia, a rural area on Oʻahu’s north shore west of Haleʻiwa.

Mokuleia is characterized by:

Agricultural lands and former sugar plantations

Strong trade winds and open coastal plains

Ancient fossil sand dunes inland from the modern shoreline

In 1976, sand from these inland dunes—not the active beach—was excavated and transported to Ala Moana. This episode is often misattributed to Magic Island’s construction; it was not. It was part of Ala Moana Beach’s maintenance decades later.

Neither Ala Moana Beach Park nor Magic Island contains ancient heiau or pre-contact sacred sites. They are products of the modern era.

Yet culturally, they became essential:

Family gatherings and picnics

Fishing, paddling, and sunset watching

Daily recreation without cost or gatekeeping

Unlike Waikīkī, these spaces remain largely free of commercialization—no hotels, no admission fees, no exclusive access.

From today’s perspective, the environmental costs were real:

Reef habitat was buried

Coastal processes were altered

Sand mining damaged distant ecosystems

But the outcome was rare: engineered coastal land that became permanent public commons.

Honolulu made this choice twice—first with Ala Moana Beach Park, then with Magic Island.

Ala Moana Beach Park and Magic Island exist because of human decisions:

Wartime necessity reshaped the coast

Engineers believed land could be made

Developers imagined profit

And, at critical moments, the City chose public access instead

Honolulu did not inherit this shoreline. It built it.

Like magic.